This essay is part of a series of reflections on primary care during the pandemic presented by Réseau-1 Québec. The original essay published in French on May 25, 2020 is available here >>

[This essay was written by the Young Leaders Committee in Patient-Oriented Research (POR), a community of early career researchers and student-researchers supporting the scientific community and its members, whose mission is to promote the next generation of POR leaders by supporting POR capacity building, networking and mentorship, scientific production, and POR knowledge translation, as well as collaboration among its members.]

The “covidification” of research

The COVID-19 pandemic has shone the collective spotlight on health research. The media report daily on scientific advances supporting the fight against COVID-19: epidemiological data, clinical trials of treatments, vaccine development, etc. Many members of the scientific community in Quebec, Canada, and internationally have mobilized to address the emerging issues of this COVID-19 crisis, to such an extent that we are witnessing a rapid “covidification” of research: major investments in research on COVID-19 (e.g. pharmaceutical, basic science, specialized medicine), the creation of networks and platforms for sharing research on COVID-19, the suspension of several non-COVID-19 research activities, the cancellation or postponement of funding competitions for non-COVID-19 studies, and the reorientation of many research teams towards COVID-19.

This “covidification” of research reflects an intention to answer pressing questions in the fight against COVID-19, but it also poses certain risks. Of course, research on epidemiology, vaccines, and treatments for COVID-19 is essential. However, it is also crucial to address issues of health service organization, quality of care, health equity, and the social aspects of this crisis. We need to avoid an “over-covidification” of research; let’s not forget that the non-COVID issues still affect patients and many challenges in our health systems have been amplified by this health crisis. Moreover, neglected or postponed health care and the delays in management of patients’ health problems will bring new challenges.

The importance of patient-oriented research

In this context, patient-oriented research (POR) is once again critically important. The upheavals we are experiencing underscore the need to produce knowledge that addresses people’s concerns. POR can produce evidence on health care services and policies oriented towards improving the health and well-being of populations and health professionals. Yet POR, which involves a strong collaborative process, is on shaky ground. During the pandemic, we need to make sure patients, health professionals, and decision-makers can continue to participate safely, and significantly, in order to ensure the production of meaningful and relevant evidence. In our post-COVID society, it will be more important than ever to maintain strong links with patient-partners so that work currently on hold can resume and adapt to the emerging challenges facing patients and the health system.

What is POR?

Patient-oriented research (POR) mobilizes patients and multidisciplinary partners, focuses on priorities established by patients, and improves patient outcomes. POR aims to apply knowledge to improve health systems and health care.

Issues for the next generation of researchers

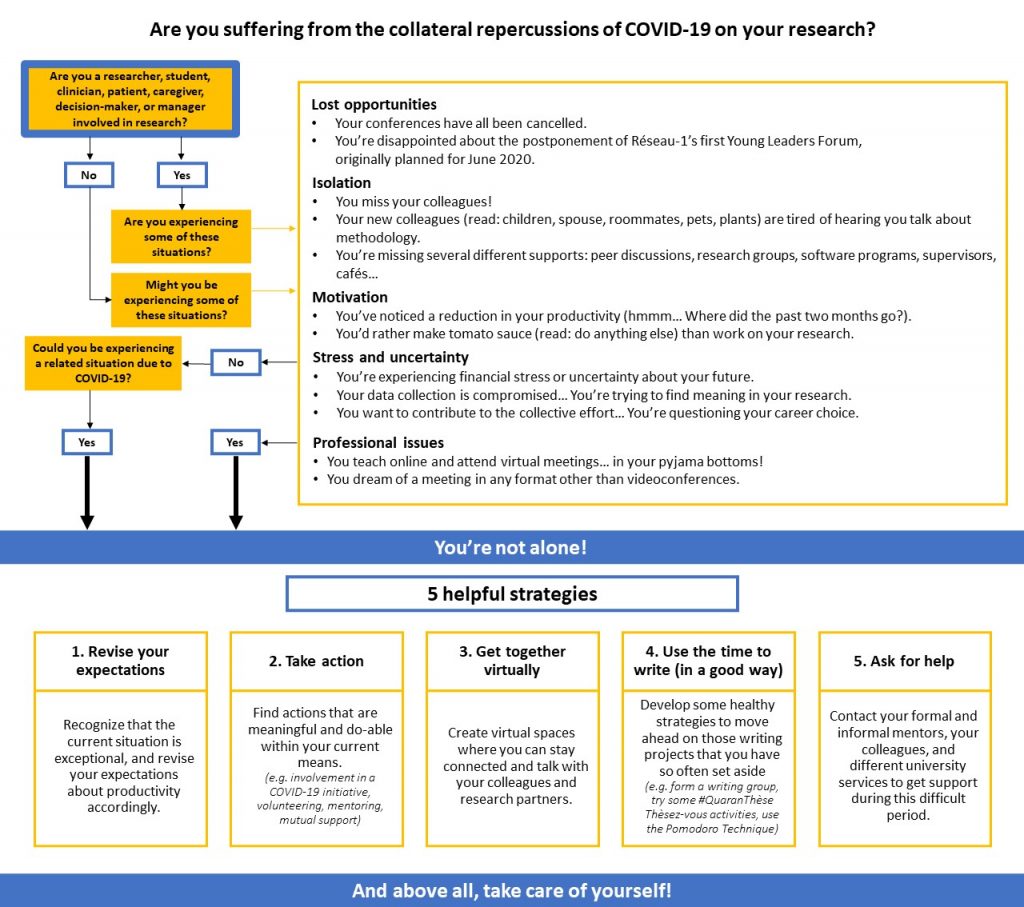

As early career researchers and student-researchers, this “covidification” of research has hit us head-on, and we are dealing with inevitable collateral effects (see our algorithm below). A loss of motivation and uncertainty about this situation have strained our capacity to be resilient and to adapt. Here are some examples of what we are experiencing: reduced job prospects and job insecurity in research; uncertain thesis defenses in formats that don’t do justice to the scope of the work and don’t allow for celebration commensurate with the effort; unreliable research funding due to the cancellation of various competitions; difficulties reconciling pro-COVID-19 research with our own research programs in a coherent manner; excessive project delays caused by the interruption of data collection; reduced ability to maintain links with patient-partners and other collaborators; the cancellation of networking events that are so valuable for our career advancement; a heavy workload generated by the move to online coursework; work–family balance issues related to working from home and the closure of schools and daycare centres; etc.

The next generation of researchers does not necessarily have the same resources and networks as experienced researchers to cope with these challenges. This situation contributes to a certain precariousness and can make research students and young researchers vulnerable.

Supporting the next generation of researchers

These upheavals contribute to weakening the next generation of researchers. Without additional support, there is a risk our generation of young researchers will crumble. Research supervisors, more experienced researchers, universities, research networks, and funding agencies all have a role to play in supporting the next generation of researchers, particularly in the current context.

It is crucial that student-researchers and early career researchers are afforded the support, flexibility, and understanding they need. Resources must be made available to us to carry out our work and plan our early career paths: more frequent follow-ups; formal and informal mentoring; support in reorienting our projects and data collection; setting priorities with regards to our objectives; flexibility in deadlines for grant and scholarship applications; consideration of work–family balance in scientific production; extension of grants and funding; etc. The creation of virtual spaces to facilitate collaboration, mutual aid, and networking can also strengthen a sense of belonging and reduce isolation. Innovative ways must be found to enable the next generation of researchers to attend training sessions, gain experience, demonstrate leadership, and engage in research. For example, the next generation can become involved in COVID-19 grant applications and projects if they are given opportunities by more experienced researchers or if their participation is encouraged by research networks and funding agencies. Granting agencies and universities could also be encouraged to show flexibility and support in maintaining and creating strategies to support the next generation of researchers in the short, medium, and long terms (e.g. competitions, funding, sponsorships, virtual events, mentoring, productivity support, career planning support).

An opportunity to rethink the research of tomorrow

As young POR researchers, we often experience discomfort and frustration with more traditional research structures and approaches that seem old-fashioned and partially out of step with the needs and realities of patients and health systems. We dream of research that is more agile, innovative, and interdisciplinary, conducted in collaboration with all holders of knowledge and experience (patients, clinicians, communities, managers, decision-makers, and researchers); research that is applied in real time to solve emerging problems, and where our performance as researchers is measured by the impact of our contributions and not just by the number of lines in our CVs. In short, “Research 3.0”, as Réseau-1 would describe it.

Amongst ourselves, we sometimes question our career choice: will research enable us to make a significant contribution to improving the health system and the well-being of populations? If the major research upheavals of recent months have proven one thing to us, it is that research can change, adapt to emerging needs, and be agile. This gives us renewed hope in research and its mission. Let’s take advantage of this crisis to rethink research, to innovate, and to make lasting changes that will maintain this agility and renewed relevance of research. We, the next generation of patient-oriented researchers, are ready to take on this challenge. Let’s not forget: we are not alone. We are part of a strong research community that is more important now than ever!

Mélanie Ann Smithman, Doctoral candidate, Université de Sherbrooke; Co-director, Capacity strengthening, Réseau-1 Québec; Fellow, Québec SPOR Support Unit

Isabelle Dufour, Nurse, Doctoral candidate, Université de Sherbrooke; Fellow, Québec SPOR Support Unit

Virginie Blanchette, Podiatrist, PhD; early-career professor, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières; POR trainee

Jean-Christophe Bélisle-Pipon, PhD, Visiting researcher, The Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics, Harvard Law School; Fellow, Health Law Institute, Dalhousie University; Invited researcher, School of Public Health, Université de Montréal; Fellow, Québec SPOR Support Unit

Samuel Turcotte, Occupational therapist; Doctoral candidate in clinical and biomedical sciences (rehabilitation option), Université Laval; Fellow, CIHR SPOR (transition to leadership stream) and Québec SPOR Support Unit

Mohamed Ali Ag Ahmed, MD-MPH, PhD; Postdoctoral fellow with the Research Chair on Chronic Diseases in Primary Care, Université de Sherbrooke

Ruth Ndjaboue, Postdoctoral trainee, Université Laval; Fellow, Diabetes Action Canada – a national patient-oriented research network

On behalf of the Young Leaders Committee in POR